Discover our history

The History of Magdalene College

Magdalene College has been a place of academic study for nearly 600 years.

One of the most common questions we receive is about pronunciation. Despite being spelt 'Magdalene' in the biblical form, the College name is pronounced 'Maudlyn'.

When Lord Audley refounded the College in 1542, he dedicated it to St Mary Magdalene. The choice of name appears to have been partly self-referential, as early documents often spell it phonetically as ‘Maudleyn’, echoing Audley’s own name. The final ‘e’ was added in the mid-nineteenth century to help distinguish Magdalene College, Cambridge, from Magdalen College, Oxford, particularly with the advent of the postal service.

Origins and Benedictine Foundations

In 1428 Abbot Lytlington of Crowland Abbey near Peterborough was licensed by Letters Patent of King Henry VI to acquire the site to establish a hostel in Cambridge for Benedictine student-monks.

The Benedictines chose a site north of the river, seeking to distance themselves from the distractions of the town. The location had a long history of settlement, with evidence of an Iron Age community nearby. Archaeological finds include parts of a Roman road, rubbish pits, coins, and the remarkable ‘Magdalene Hoard’ of medieval coins, now housed in the Fitzwilliam Museum.

Construction began in the 1470s under John de Wisbech, Abbot of Crowland, who planned First Court and completed the Chapel. The Benedictines funded the communal buildings, while individual abbeys were responsible for their own student accommodation. Four local abbeys—Crowland, Ely, Ramsey, and Walden—each built a two-storey staircase, three of them in the south range.

After 1472, the institution became known as Buckingham College, reflecting the patronage of Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham. However, this association proved unfortunate when the Duke was executed for treason in 1483.

In time, lay students were admitted, renting rooms from the host abbey. Among them was Thomas Cranmer, later Archbishop of Canterbury, who was appointed a lecturer at Magdalene in 1515.

Buckingham College and Tudor Transformations

In 1519, Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham, funded the construction of the College Hall. At 41, he was likely preparing to endow Magdalene generously, but his plans were cut short. In 1521, like his father before him, he was executed for treason.

It would be another two decades before the College found a major benefactor. In the meantime, Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries led to the closure of Crowland Abbey in December 1539. Despite this, Magdalene remained open, avoiding the disruption that affected many monastic institutions.

One of the Benedictine abbeys linked to the College, Walden, came into the possession of Thomas, Lord Audley. A former Speaker of the House of Commons, Audley had risen to power as Lord Chancellor, overseeing the trials of Sir Thomas More and Bishop John Fisher, and playing a role in Henry VIII’s dealings with his wives and ministers, including Thomas Cromwell.

Having secured a grand residence at Audley End, a peerage, and membership of the Order of the Garter, Audley re-founded Buckingham College as the College of St Mary Magdalene in 1542. The College arms, featuring the motto Garde ta foy ("Keep faith") and a wyvern crest, were taken from Audley’s own.

Once again, Magdalene suffered the misfortune of losing its patron too soon. Audley died in 1544 at the age of 56, leaving behind a College in financial difficulty. The street front was later completed in the 1580s, thanks to the generosity of Sir Christopher Wray, Chief Justice of the Queen’s Bench.

Financial Struggles and the Spinola Affair

When Audley refounded Magdalene, he granted the College seven acres of land at Aldgate in the City of London—a reward from Henry VIII for his role in disposing of Anne Boleyn.

Had this property remained in the College’s possession, it would have provided significant financial security. However, in 1574, it was permanently lost to the Crown due to the manoeuvring of an Elizabethan banker, Spinola.

Spinola enticed the Master and Fellows with the seemingly attractive prospect of increasing the annual rent from £9 to £15. Many believed the transaction to be unlawful, and the College repeatedly challenged it in court. The first such lawsuit, pursued with determination by Barnaby Goche (Master 1604–26), resulted in both him and the Senior Fellow being imprisoned for two years. When Goche was later offered £10,000 to settle the dispute, he refused.

By 1880, compulsory purchases for railways and sewers had reduced even that modest rent further, leaving the College with only a nominal £2 per year from what should have been its primary endowment.

When the Quayside development was completed in 1989, Magdalene marked the occasion by commissioning Fluck and Law, creators of Spitting Image, to sculpt an unflattering gargoyle of Spinola, which now spouts water into the Cam.

Samuel Pepys and the 17th Century

The future diarist Samuel Pepys joined Magdalene in 1650. Unsurprisingly, he soon clashed with the puritanical authorities and was reprimanded by his tutors for being "scandalously overseene in drink the night before."

As his famous diaries reveal, his habits did not change much over time, but that did not hinder a distinguished career in Restoration London. He became a Member of Parliament, a Baron of the Cinque Ports, an influential Secretary to the Admiralty—where he played a key role in the early professionalisation of the Royal Navy—and was elected President of the Royal Society in 1684.

Pepys’ diary, written between 1660 and 1669, remains a vital historical source, offering unique insights into England during the years following Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth. His first-hand accounts of events such as the Restoration of Charles II and the Great Fire of London provide an extraordinary window into the period.

A generous benefactor to Magdalene, Pepys contributed three times to the construction of the new College building that now bears his name. Work on the elegant addition to Second Court began in 1670, though fundraising was slow. By the time of Pepys’ death in 1703, the building was largely complete and became the perfect home for his final bequest: a remarkable collection of books and papers that now form the Pepys Library.

Enlightenment and Social Reform

Daniel Waterland, Master from 1714, was a leading theologian who introduced a forward-thinking curriculum at Magdalene. His reforms included Mathematics, Newtonian Physics, Geography, and Astronomy alongside Classics, Logic, and Metaphysics.

He also secured funding for scholarships, including the Millington scholarships, which attracted Edward Waring, one of the finest mathematicians of the century. Waring, a predecessor of Stephen Hawking as Lucasian Professor, was renowned across Europe for his mathematical work.

Despite Waterland’s efforts, the College’s fortunes declined after his death. In the middle decades of the eighteenth century, the number of undergraduates sometimes dropped to single figures. It was not until Dr Peter Peckard became Master in 1781 that Magdalene began to regain its standing. A progressive churchman, Peckard championed social justice, particularly through his powerful sermons against the slave trade.

His words, delivered before the University in 1790, remain striking:

"What a contradiction to these gracious intentions is the whole of our conduct respecting the innocent and unoffending nations of Africa! if we consider the treatment they receive from us; first by being torn from their country and their friends by the violence of hardhearted ruffians, then doomed to chains and excruciating misery, and if they survive these calamities, in being sold for Slaves to merciless masters, not less cruel than the ruffians who forced them from their native land. Is this our Gospel of Peace and Liberty?"

From the 1790s onwards, Magdalene produced several figures central to the abolitionist and early human rights movements. Sir George Stephen led the campaign for the abolition of slavery in 1833, while Samuel Marsden brought the Christian mission to New Zealand in 1814.

Waterland’s reforms found an echo in the early nineteenth century with William Farish, who introduced the first written university examination. Though a chemist by training and Jacksonian Professor of Natural Philosophy, Farish is often considered the first university lecturer in Engineering—a field in which Magdalene continues to excel today.

Victorian Magdalene

Although not the smallest College, Magdalene was undoubtedly the poorest during the Victorian period. This may explain why relatively few eminent scholars and public figures emerged at the time.

However, the College was notably ahead of its peers in widening access. It admitted Catholics, including Charles Acton (later Cardinal), and Arthur Cohen, the first practising Jewish Cambridge graduate, who went on to become a leading barrister. Magdalene also welcomed Asian students at a time when many other Colleges still excluded them—a practice that persisted elsewhere until after the First World War.

One of the most influential figures of Victorian Magdalene was Charles Kingsley, who joined in 1838. A clergyman and social reformer, he became Regius Professor of Modern History in 1860 and was an early advocate of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. He is best remembered today as a novelist.

Another supporter of Darwin’s ideas was Kingsley’s younger contemporary, Alfred Newton, who entered Magdalene in 1848 and remained closely associated with the College for the rest of his life. Appointed the University’s first Professor of Zoology in 1866, he lived in Old Lodge until his death in 1907.

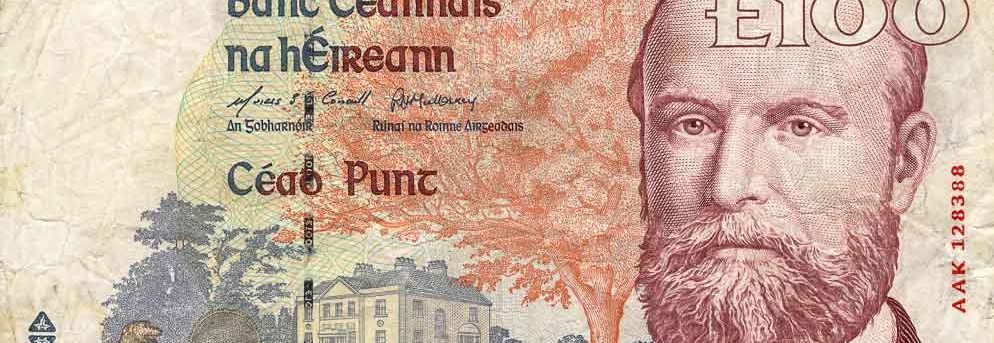

Perhaps the most significant figure to attend Magdalene in the latter half of the nineteenth century was Charles Stewart Parnell. A student from 1865 to 1869, he became the leader of the Irish nationalist movement. Today, the College maintains the prestigious Parnell Fellowship in Irish Studies in his honour.

Detail of the old Bank of Ireland £100 note depicting Charles Stewart Parnell

The 20th Century Renaissance

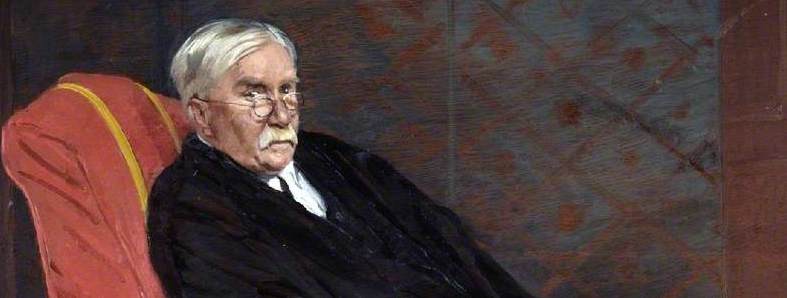

The twentieth century marked a turning point in Magdalene’s fortunes, thanks in large part to the groundwork laid by A. C. Benson.

A Fellow from 1904 and Master from 1915 to 1925, Benson’s boundless enthusiasm, literary output, and financial generosity left a lasting imprint on the College. His influence on its buildings is evident—his arms or initials appear no fewer than twenty times around the site.

Throughout the century, Magdalene graduates excelled across a range of professions. Patrick Blackett arrived at the College in 1919 after serving in the First World War and later won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1948. Geoffrey Webb became Slade Professor of Fine Art and played a key role in the preservation of European heritage during the Second World War, inspiring the 2014 film The Monuments Men. Kingsley Martin, another contemporary, became a prominent journalist and edited the New Statesman for thirty years.

Magdalene also played a central role in the development of English Studies. I. A. Richards, often called the ‘founding father’ of modern literary criticism, began his studies at the College in 1911. He collaborated with C. K. Ogden, a fellow Magdalene graduate who pioneered ‘Basic English’, a simplified form of the language that remains influential in English teaching worldwide. One of Richards’ early students, the poet and critic William Empson, was less fortunate—he was expelled when condoms were found in his room. The College made amends fifty years later, electing him to an honorary fellowship in 1979.

Several major literary figures became Honorary Fellows, including Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, T. S. Eliot, and Seamus Heaney. C. S. Lewis was a Professorial Fellow from 1954 to 1963 and lived in First Court above the Parlour and Old Library.

Detail from William Nicholson's portrait of A. C. Benson, in the collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum.

The 20th Century Renaissance Continued

Magdalene has also been home to social pioneers. Antony Grey, who studied History from 1945 to 1948, played a vital role in the campaign to decriminalise homosexuality in the UK. Lord Arran, who introduced the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, credited Grey as having ‘done more than any single man’ to bring about reform.

In 1987, Magdalene became co-educational, welcoming its first women undergraduates the following year. Among them was broadcaster Katie Derham, later a contestant on Strictly Come Dancing and now a Magdalene Honorary Fellow.

Towards the end of the century, the College continued to produce leading scholars. Sir John Gurdon, Master from 1995 to 2002, later won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 2012.

The Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to Kipling in 1907, Eliot in 1948, and Heaney in 1995.

Magdalene in the 21st Century

The early 21st century has seen significant developments at Magdalene, enhancing both academic and student life.

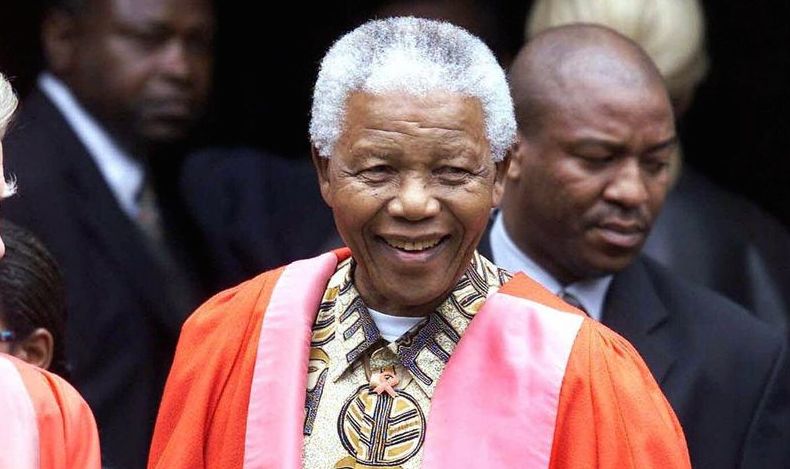

A highlight of the new millennium was the admission of Nelson Mandela as an Honorary Fellow. President Mandela visited Magdalene in 2001, where he met some of the holders of the College's Mandela-Magdalene scholarships. His legacy continues to grow, with the establishment in 2017 of the Magdalene Mandela Memorial Fellowship alongside the first Professorship of the Deep History and Archaeology of Africa, generously endowed by the Jonathan and Jennifer Oppenheimer Foundation.

In 2005, the College completed the Cripps Court development on Chesterton Road, providing a lecture theatre, seminar rooms, and modern conference facilities, alongside high-quality student accommodation. This and other expansion projects ensure that Magdalene can continue to house all undergraduates and nearly all postgraduates within a short walk of the main College site.

The New Library, completed in 2021, provides a dedicated 24/7 space for study, collaboration, and inspiration. It houses the College’s working library, the College Archives and Ronald Hyam Archive Work Room, and The Robert Cripps Art Gallery. The following year, the New Library was awarded the prestigious The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Stirling Prize for the UK’s best new building.

Nelson Mandela at Magdalene in 2001.